The Aztec civilization worshipped a complex pantheon of gods and goddesses who ruled over every aspect of life and nature.

These powerful deities controlled everything from the sun’s journey across the sky to the growth of crops and the arrival of rain.

Understanding these gods helps us appreciate the rich spiritual world that shaped Aztec culture and their understanding of the universe around them.

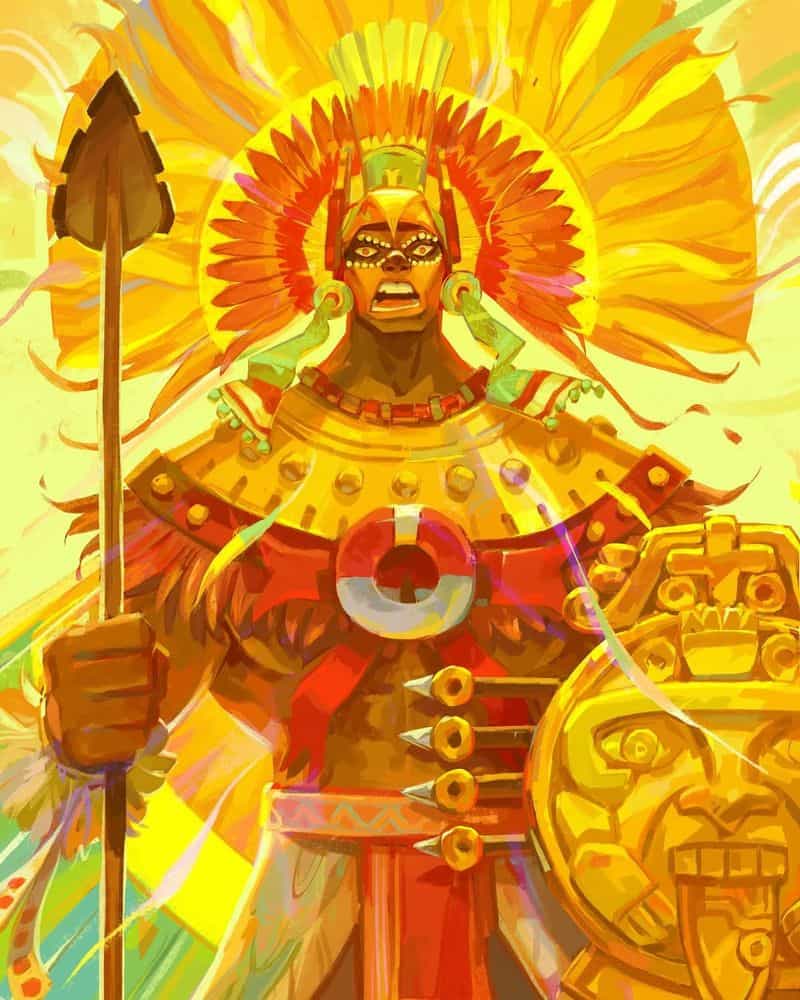

1. Huitzilopochtli: The Warrior Sun God

Born fully armed from his mother Coatlicue, Huitzilopochtli emerged as the fiercest deity in the Aztec pantheon. The Aztecs believed he guided them to their homeland Tenochtitlan and required human sacrifice to maintain his strength for battling darkness each night.

As the sun god, he carried the heavy responsibility of ensuring the sun rose each morning. Without regular offerings of human hearts and blood, Aztecs feared Huitzilopochtli would grow weak, causing the sun to falter and plunging the world into eternal darkness.

Warriors who died in battle or sacrifice joined his eternal retinue, making a battlefield death the most honored fate for Aztec men.

2. Quetzalcoatl: The Feathered Serpent

Feathers of the resplendent quetzal bird adorning a serpent’s body created one of Mesoamerica’s most beloved deities. Quetzalcoatl represented wisdom, creation, and the arts, serving as patron to priests, merchants, and craftspeople throughout the Aztec Empire.

Ancient stories tell how he sacrificed himself to create the current world and humanity. After burning himself to death, his heart rose to become the morning star Venus, connecting earth and heaven.

Many historians believe the Aztec emperor Montezuma initially mistook Spanish conquistador Cortés for the returning Quetzalcoatl, as prophecies foretold the god would someday return from the east with pale skin.

3. Tlaloc: Master of Rain and Lightning

Recognizable by his goggle-like eyes and fanged teeth, Tlaloc commanded the life-giving rains essential to Aztec agriculture. Farmers looked to him for bountiful harvests, while fearing his wrath in the form of floods, lightning strikes, and devastating droughts.

Children sacrificed to Tlaloc were a special category of honored dead. The Aztecs believed their tears during sacrifice pleased the rain god, and that these young souls would enjoy a paradise-like afterlife in Tlalocan, his verdant realm.

Mountain shrines dedicated to Tlaloc contained precious water-related offerings. Even today, his image adorns the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, symbolizing his enduring importance.

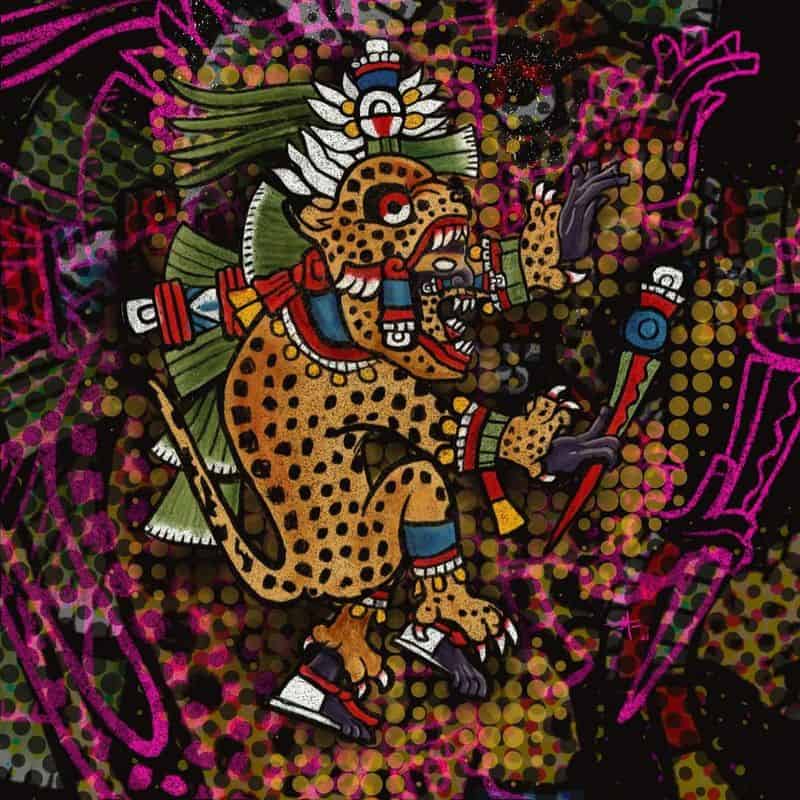

4. Tezcatlipoca: The Smoking Mirror

Known as “The Smoking Mirror,” Tezcatlipoca watched mortals through his obsidian mirror, seeing into their hearts and judging their actions. Missing one foot, which he sacrificed to bait the earth monster, he often appeared as a jaguar, embodying night’s stealth and power.

Young warriors feared and respected him as the deity of rulers, sorcerers, and night. His annual festival featured a handsome young man living as Tezcatlipoca’s embodiment for a year before willing sacrifice, representing the god’s unpredictable nature.

Rivals and brothers, Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl engaged in an eternal cosmic struggle, taking turns destroying and rebuilding the world through different eras or “suns.”

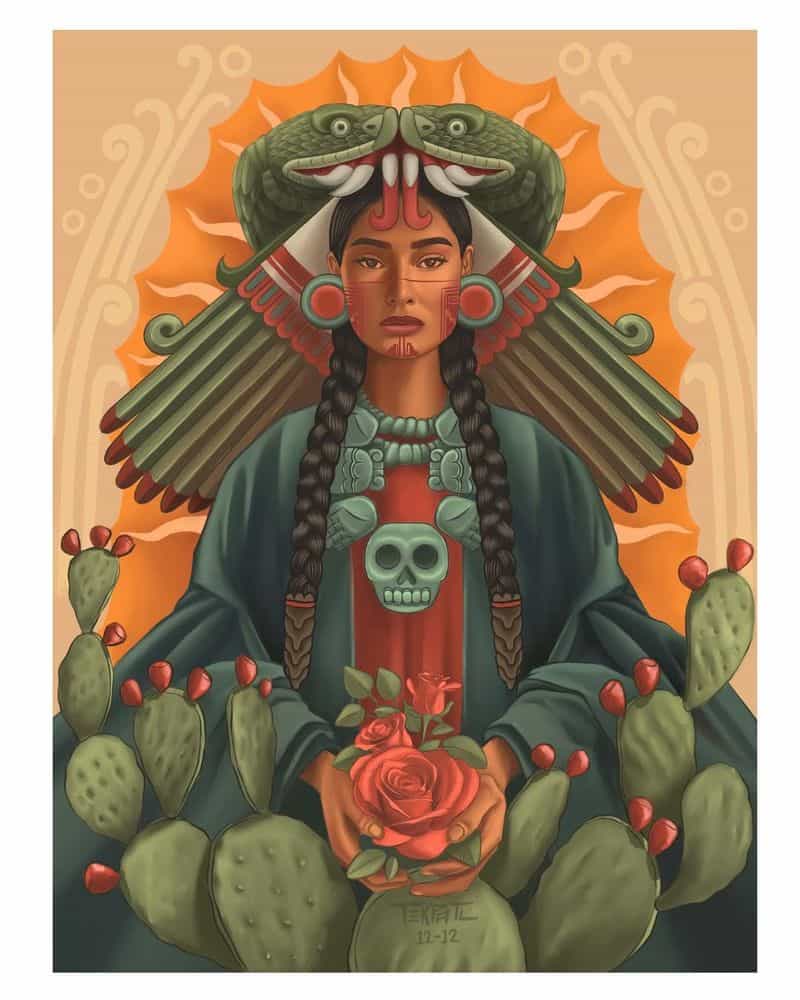

5. Coatlicue: The Mother of Gods

Wearing her signature skirt of writhing snakes and necklace of human hearts and hands, Coatlicue embodied the terrifying duality of creation and destruction. Her severed head sprouted twin serpents, symbolizing the flowing blood that nourishes the earth while reminding mortals of death’s constant presence.

Mythology tells how she miraculously conceived Huitzilopochtli after a ball of feathers touched her while sweeping a temple. Her older children, led by her daughter Coyolxauhqui, plotted to kill her for this dishonor, but the fully-armed Huitzilopochtli sprang from her womb to defend her.

The massive Coatlicue stone statue discovered beneath Mexico City’s central plaza in 1790 still inspires awe with its powerful, unsettling imagery.

6. Xipe Totec: The Flayed One

Golden corn husks inspired the disturbing imagery of Xipe Totec, who wore flayed human skin like a corn plant sheds its outer layers. Farmers celebrated this agricultural deity during spring festivals when priests donned the skins of sacrificial victims, embodying the earth’s renewal.

His name translates to “Our Lord the Flayed One,” reflecting his self-sacrifice of cutting off his own skin to feed humanity. This painful act represented the necessary suffering required for new growth and abundance.

Red-painted statues of Xipe Totec show him wearing human skin with the hands dangling at the wrists and torn-open eye holes, symbolizing how life emerges from death in the eternal cycle of seasons.

7. Mictlantecuhtli: Ruler of the Underworld

Skeletal and terrifying, Mictlantecuhtli reigned over Mictlan, the underworld where most ordinary Aztecs would journey after death. His exposed bones, blood-spattered body, and necklace of human eyeballs emphasized his connection to death and decay.

Souls journeying to his realm faced a challenging four-year journey. They needed to cross rivers of blood, climb obsidian mountains, and brave freezing winds while avoiding fearsome creatures before reaching their final rest in Mictlan’s nine layers.

Despite his frightening appearance, Mictlantecuhtli wasn’t considered evil. The Aztecs viewed him as a necessary force in the cycle of life, death, and rebirth, similar to how fallen leaves nourish new growth.

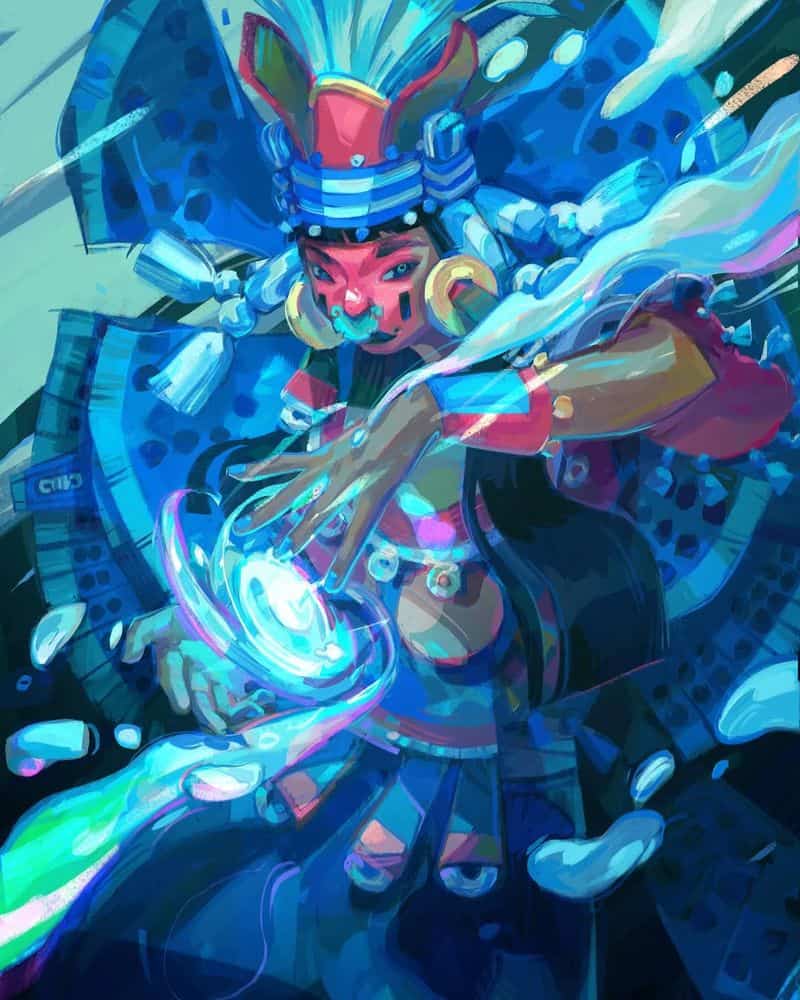

8. Chalchiuhtlicue: Goddess of Waters

Adorned with jade ornaments and a flowing blue skirt representing rivers and lakes, Chalchiuhtlicue brought life-giving water to the Aztec world. Her name translates to “She of the Jade Skirt,” reflecting her association with precious water and fertility.

Mothers sought her blessing during childbirth, believing she washed away sin from newborns. Priests performed water rituals in her honor, recognizing that without her benevolence, crops would fail and people would perish from thirst.

According to creation myths, Chalchiuhtlicue presided over the Fourth Sun or world era, which ended when she unleashed a great flood that transformed humans into fish – a reminder of her power to both nurture and destroy.

9. Xochiquetzal: Goddess of Beauty and Love

Eternally youthful and surrounded by butterflies and flowers, Xochiquetzal embodied feminine beauty, love, and artistic creation. Weavers, embroiderers, painters, and sculptors prayed to her for inspiration and skill in their crafts.

Married women seeking fertility wore her emblems and participated in her festivals, dancing with flowers in their hair. Young women looked to her as a patron of romantic love and marriage, though she also had a wilder side as the first being who discovered pleasure.

Myths tell how she was originally a fertility goddess who was kidnapped by Tezcatlipoca and taken to the heavens. This tale explained the origin of romantic desire and the sometimes painful nature of love’s pursuit.

10. Tonatiuh: The Fifth Sun

Golden rays emanate from Tonatiuh’s fierce face at the center of the famous Aztec Sun Stone, marking him as the current sun deity of the Fifth Age. The Aztecs believed his daily journey across the sky required nourishment in the form of human hearts and blood.

Warriors who died in battle and sacrificial victims had the honor of joining Tonatiuh’s celestial court. They would accompany him on his daily journey from sunrise to noon, when female warriors who died in childbirth would escort him through the afternoon and into the underworld.

His name means “He Who Goes Forth Shining” in Nahuatl. The distinctive face on the Sun Stone, with a sacrificial knife for a tongue, remains one of the most recognizable symbols of Aztec religion today.

Lover of good music, reading, astrology and making memories with friends and spreading positive vibes! 🎶✨I aim to inspire others to find meaning and purpose through a deeper understanding of the universe’s energies.