Once, they were worshiped — gods of rain, love, death, and fire — fed by offerings, prayers, and fear.

Temples rose in their honor, songs were sung in their names, and entire civilizations built moral codes around their myths.

But time is cruel to deities. When the people fade, their gods fade with them, or worse, they survive as monsters.

Across the world’s mythologies, the same story repeats: divine beings turned to demons, holy names rewritten as curses.

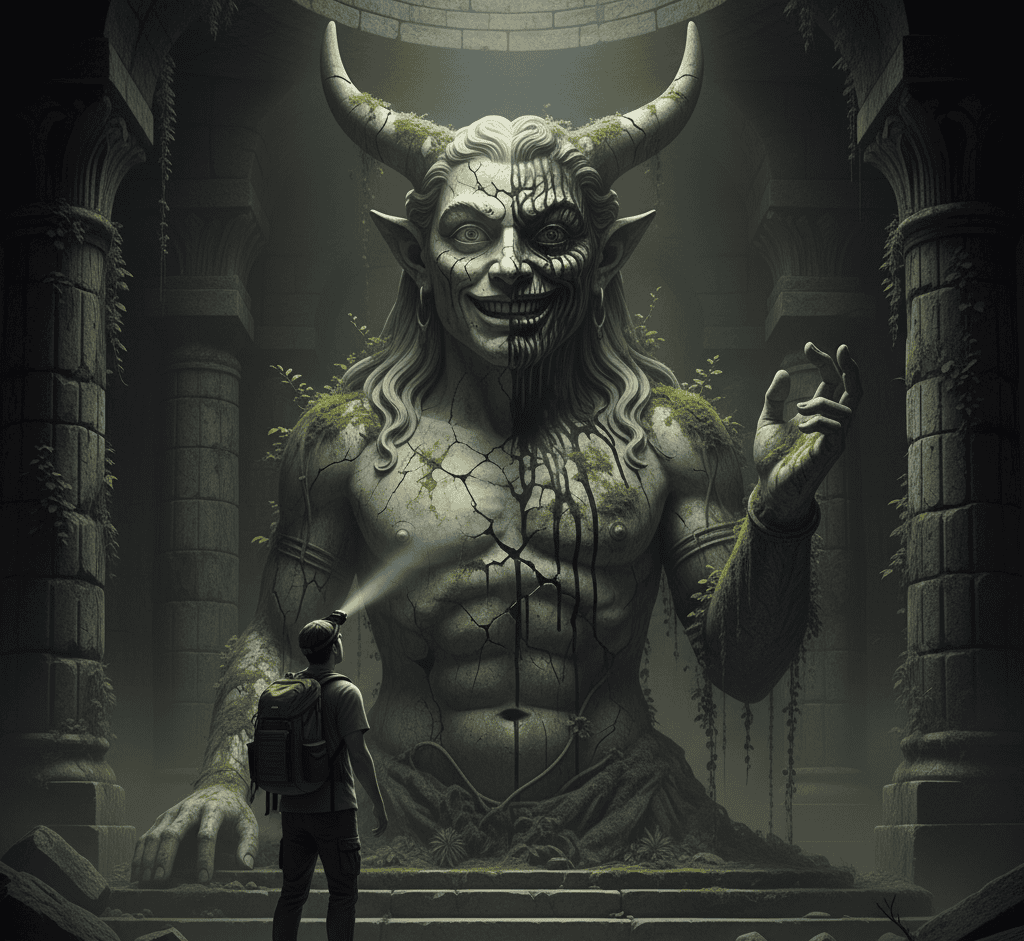

What happens when faith dies, but the memory of power remains?

When a God Outlives Its People

Civilizations vanish, but their gods often refuse to go quietly. When a new religion rises, it rarely erases the old completely.

Instead, it repurposes. The conqueror’s god becomes the symbol of truth, and the conquered gods are painted as lies, tricksters, or embodiments of evil.

This transformation isn’t just theology, it’s survival. Old deities must either adapt to the new spiritual order or become its enemies.

What was once sacred becomes forbidden, and in that act of rewriting, gods begin to rot into demons.

Take the ancient Near East, where the line between gods and demons was always thin.

Ba’al, once a powerful Canaanite storm god, became Beelzebub — “Lord of the Flies” — in Hebrew texts, later evolving into one of Hell’s princes in Christian demonology.

In Mesopotamia, the goddess Lamashtu, a terrifying yet divine figure who protected mothers by punishing the wicked, became a purely malevolent demon in later traditions.

To the new faiths, it was a necessary transformation. To the old gods, it was exile.

The Politics of Damnation

Demonization often begins not in myth, but in politics. Religion is power, and power needs hierarchy.

When empires expand, they bring their gods with them and demote the gods of others.

In early Christianity’s spread across Europe, local gods and spirits of the forest, rivers, and mountains were recast as devils or witches’ familiars.

The Celtic horned god Cernunnos became the prototype for the Christian devil’s horns. In Slavic lands, Veles, god of the underworld and cattle, was recast as a serpent-demon opposing the new sky-god cult of Perun.

These weren’t coincidences. Missionaries and rulers understood that to erase a people’s faith, you must turn their beloved gods into something fearful.

If a farmer who once prayed to Veles for healthy livestock was told that the same being now serves Satan, fear replaces reverence, and power changes hands.

But the strangest irony is that these “demoted” gods never fully disappear. They linger in language, in superstition, in the corners of villages where people still whisper their names under their breath.

The Memory Trap

Psychologically, humans struggle to forget what they fear. Fear anchors memory. When a god becomes forbidden, it often becomes mais forte in the imagination.

This is why so many demon legends retain divine echoes — horns of fertility gods, wings of messenger deities, or serpentine forms linked to creation myths.

The transformation from god to demon is never a full erasure; it’s a distortion.

In medieval Europe, many demons cataloged by church scholars were clearly repurposed deities.

The demon Astaroth, described as a vile duke of Hell, was once Astarte, the Phoenician goddess of love and war — an analogue of Ishtar.

The demon Lucifuge Rofocale, whose name means “he who flees the light,” echoes older solar gods dethroned by monotheism.

The process is almost psychological: humanity projects its guilt, fear, and need for moral clarity onto the divine.

When we can’t reconcile a god’s complexity, we split it into two. The good half becomes saintly or angelic. The dark half becomes demonic.

From Divine to Diabolical

The linguistic roots of many “demons” reveal their sacred origins. The Greek word daimon originally meant a guiding spirit — not evil, merely supernatural.

Socrates even spoke of his daimonion, a divine inner voice that advised him.

Only later did “demon” acquire its moral stain, largely through early Christian reinterpretation of pagan beliefs.

In Hinduism, a similar divide exists between devas (gods) and asuras (anti-gods). Yet in the oldest Vedic texts, both groups were divine.

The split into “good” and “evil” came later as cultural power shifted between tribes and theological schools. What one group saw as its gods, another saw as its enemies.

Even within Christian tradition, there’s tension around what counts as divine rebellion.

Lucifer’s fall, for instance, mirrors countless older myths where gods of light or knowledge are cast down — Prometheus stealing fire, Enki giving wisdom to humanity, Quetzalcoatl teaching civilization.

The fallen figure isn’t merely evil; he represents the forbidden divine, the memory of power that refuses obedience.

The Ghosts of the Old World

All over the world, remnants of forgotten gods haunt folklore. In the Balkans, rural legends of vile (winged women of the woods) may stem from pre-Christian fertility or weather goddesses.

In Ireland, the Tuatha Dé Danann, once mighty deities, were demoted to fairy folk, tricksters hiding in hills after losing the world to mortals.

In the Middle East, the jinn once included powerful nature and ancestor spirits, neither good nor evil.

But later monotheistic theology divided them into obedient or rebellious, making half of them demons aligned with Iblis.

Even in modern times, traces remain. Words like “hellhound,” “faerie,” or “witch” all echo divine origins twisted by cultural fear.

When a god’s temple crumbles, its myth seeks new shelter, often in nightmares.

Demonization as Cultural Memory

To demonize an old god is to remember it in negative form — a kind of cultural scar.

It’s proof that memory can’t be deleted, only inverted. When historians or theologians label a being as evil, they’re often preserving what was once sacred under a new symbol.

The phenomenon also reveals something uncomfortable about human nature: we define ourselves by our enemies as much as by our heroes.

A new religion doesn’t just need a savior, it needs something to save people from.

The old gods fill that role perfectly, already familiar enough to inspire fear, yet distant enough to condemn.

In that way, the demonization of forgotten gods is a story of continuity disguised as opposition. The so-called devils of one faith are often the ancestors of its angels.

The moral inversion hides an unbroken lineage of spiritual archetypes: the teacher, the destroyer, the bringer of storms, the keeper of secrets.

The Return of the Forgotten

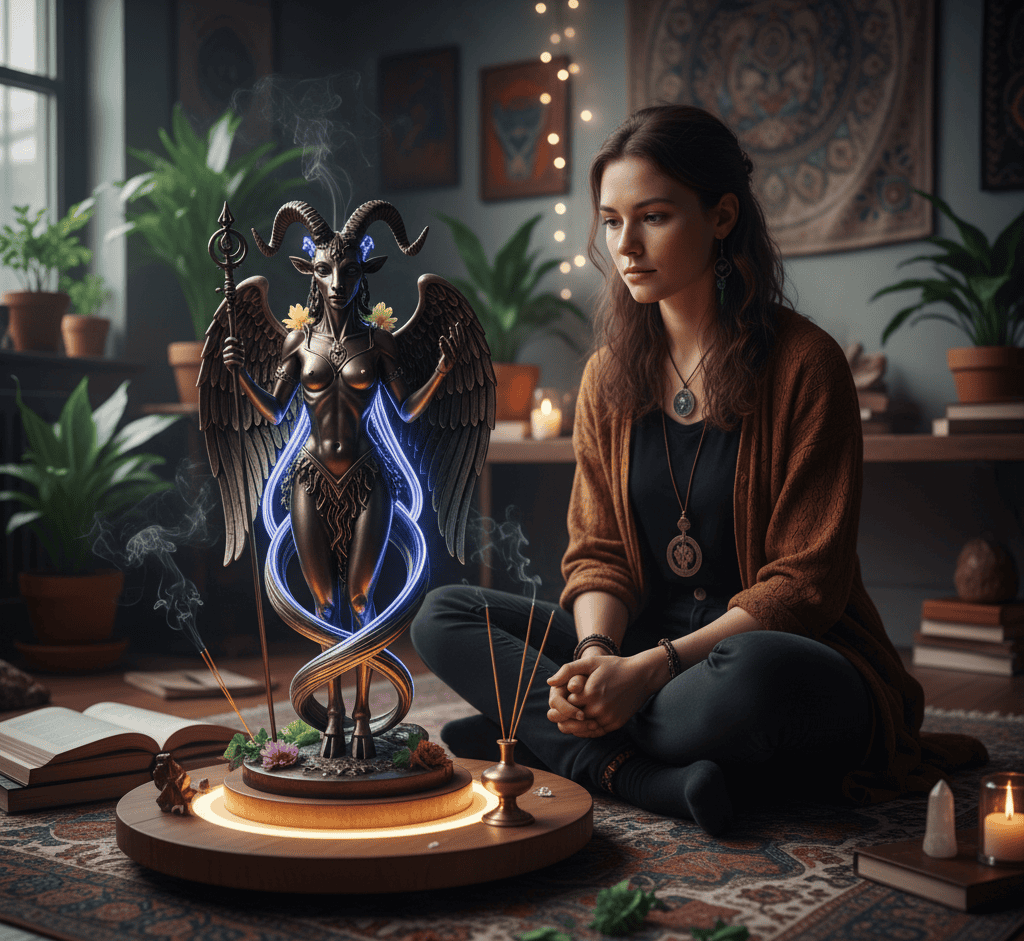

In the last century, something unexpected has happened — the forgotten gods are coming back.

Through modern paganism, occult revival, and the internet’s global folklore exchange, deities once labeled demonic are being reclaimed.

Practitioners of neopaganism honor gods like Pan, Hecate, and Lilith without the stigma of sin.

Scholars reinterpret ancient myths through archaeology and linguistics, peeling away centuries of moral revisionism.

Even in popular culture, figures like Loki, Medusa, and Lucifer are portrayed with complexity, not pure evil. But with this revival comes caution.

To resurrect old gods is to awaken forgotten moral systems, the ones that existed before “good” and “evil” were cleanly divided.

These beings demand balance, offering gifts with one hand and chaos with the other. To remember them properly means accepting that the divine is rarely gentle.

Sempre senti uma forte ligação com o Divino desde o meu nascimento. Como autora e mentora, a minha missão é ajudar os outros a encontrar o amor, a felicidade e a força interior nos momentos mais sombrios.