The Enlightenment era, spanning roughly from the late 1600s to the early 1800s, was supposed to be all about reason and science. But even the smartest folks back then believed some pretty weird stuff!

While they were busy questioning old ideas and making amazing discoveries, they also clung to some truly head-scratching theories that make us giggle today.

Let’s explore these strange beliefs that even the brightest minds of the Age of Reason couldn’t shake off.

1. Tiny Humans Living in Sperm

Scientists peering through early microscopes thought they saw miniature humans curled up inside sperm cells! This bizarre theory, called preformationism, suggested each sperm contained a fully-formed tiny person (homunculus) just waiting to grow.

The homunculus supposedly had all its body parts intact – just incredibly small. Some even believed these tiny humans had their own even tinier sperm containing even tinier humans, creating an infinite Russian doll situation.

Dutch scientist Nicolaas Hartsoeker drew famous illustrations of these imaginary beings in 1694, though he admitted he couldn’t actually see them. This wacky idea persisted until proper embryology developed in the 19th century.

2. Bloodletting as a Miracle Cure

Got a headache? Feeling feverish? During the Enlightenment, doctors would likely suggest draining your blood! Bloodletting ranked as medicine’s go-to treatment for practically everything from pneumonia to indigestion.

Physicians believed illnesses resulted from an imbalance of four bodily “humors” – blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. By draining excess blood, they thought they were restoring natural harmony. Special bleeding bowls even featured measurement lines to track exactly how much blood was removed.

George Washington famously died after doctors drained nearly half his blood to treat a throat infection. Despite killing countless patients, this practice remained popular until the mid-1800s.

3. Spontaneous Generation of Life

Maggots appearing in meat? Obviously they just formed from nothing! Many Enlightenment thinkers genuinely believed living creatures could spontaneously generate from nonliving matter without parents or eggs.

Recipe books even included instructions for creating mice: just place sweaty underwear and wheat in an open jar, wait 21 days, and voilà – mice! People thought frogs emerged from mud, insects from morning dew, and eels from river sludge.

Italian physician Francesco Redi challenged this notion in 1668 with his famous meat experiment, showing flies laid eggs that became maggots. Yet the belief persisted until Louis Pasteur finally demolished it nearly 200 years later!

4. Earth’s Hollow Interior Civilizations

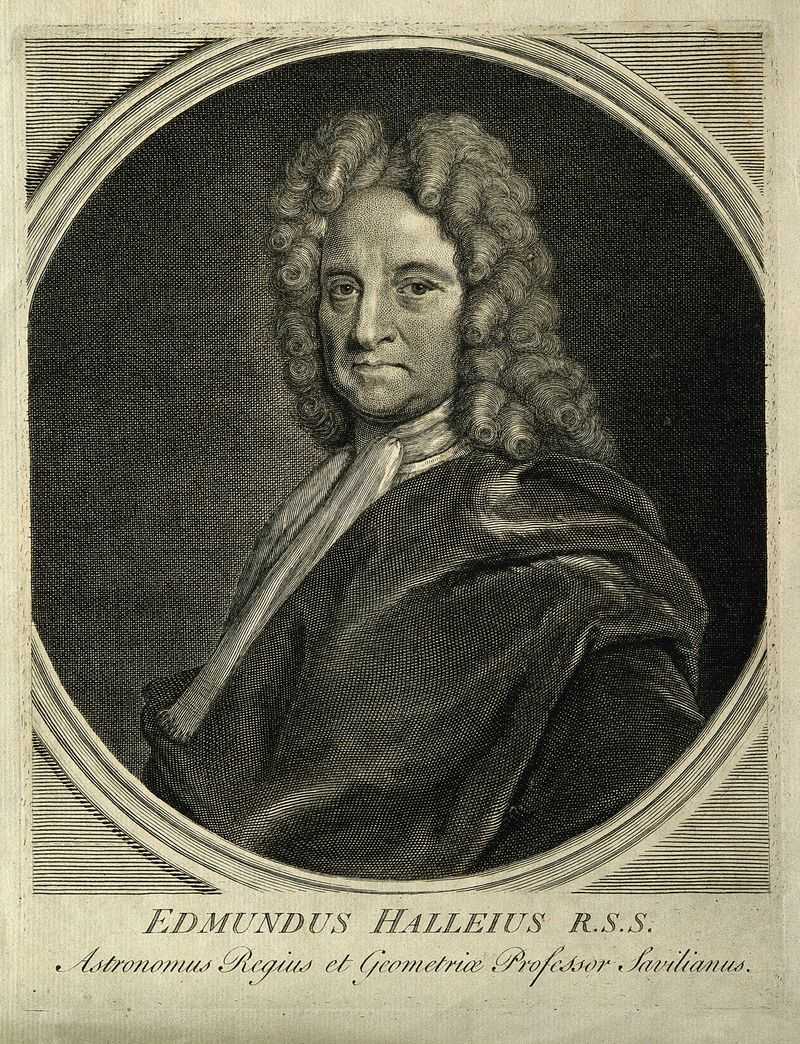

Long before science fiction writers imagined underground worlds, respected Enlightenment scientists proposed our planet was actually hollow! Astronomer Edmond Halley (yes, the comet guy) suggested in 1692 that Earth contained several concentric shells with habitable regions between them.

Halley wasn’t alone in this peculiar thinking. John Cleves Symmes Jr. later campaigned for an expedition to the North Pole, where he believed they’d find an entrance to this inner world populated by advanced civilizations.

The hollow Earth theory spawned wild speculation about mysterious beings dwelling beneath our feet. Some even suggested sunlight entered through holes at the poles, creating perfect living conditions for these subterranean societies!

5. Animal Magnetism Healing Powers

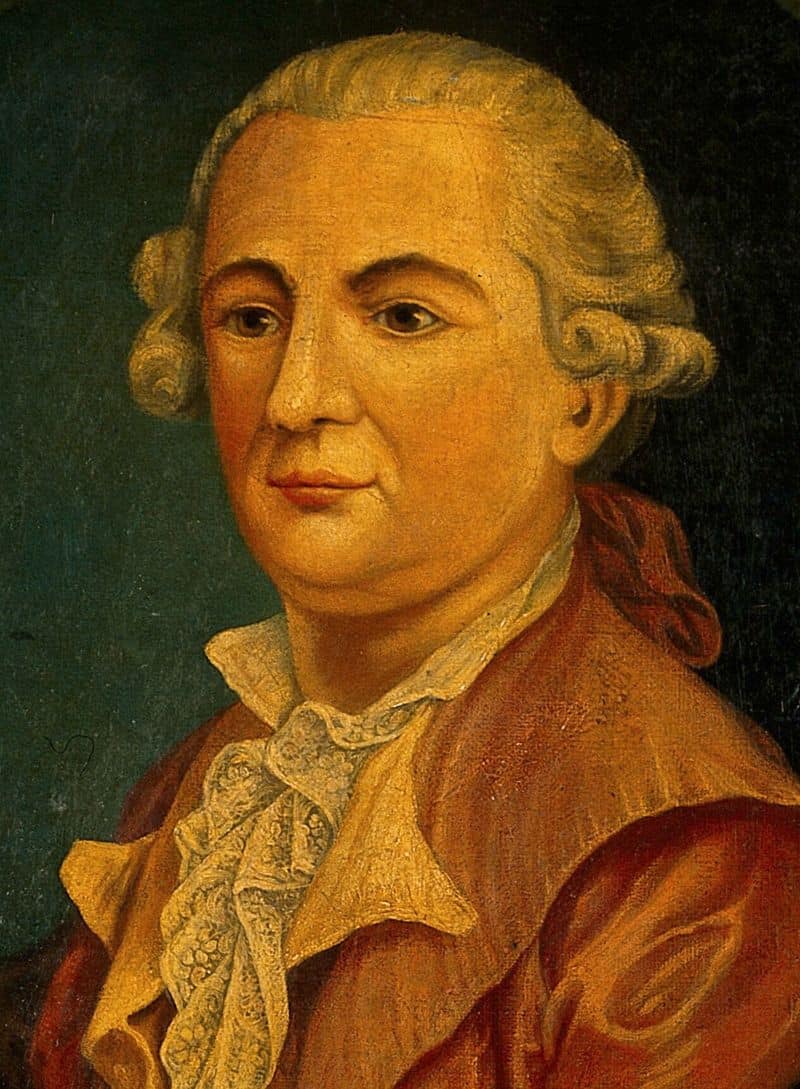

Franz Mesmer had Enlightenment Paris swooning over his bizarre healing sessions! This Austrian physician claimed to manipulate an invisible magnetic fluid flowing through all living beings, which he called “animal magnetism.”

Mesmer’s treatments involved patients sitting around a tub filled with iron filings and water while he waved magnetic wands over them. Many patients experienced convulsions or fell into trance-like states during these group sessions, which were especially popular among fashionable women.

Though a scientific commission including Benjamin Franklin debunked Mesmer’s claims in 1784, his legacy lives on in the word “mesmerize.” His work also laid groundwork for later studies of hypnosis and suggestion.

6. Phlogiston: The Fire Element

What makes things burn? For most of the Enlightenment, scientists were convinced it was an invisible, weightless substance called phlogiston! According to this theory, combustible materials contained phlogiston that was released during burning.

The weirder part? Scientists believed when something burned, it actually lost weight by releasing this mysterious substance. When experiments showed burning metals gained weight instead, phlogiston defenders claimed it had “negative weight” – defying gravity!

For nearly a century, chemists built elaborate explanations around phlogiston until Antoine Lavoisier finally demonstrated in the 1770s that combustion involved oxygen combination rather than phlogiston release. This revelation helped launch modern chemistry.

7. Bad Air Causing Disease

The smell of sewage making you sick? Enlightenment doctors would agree – they believed diseases spread through foul-smelling “miasma” or bad air! This miasma theory explained why diseases like cholera and plague seemed to thrive in filthy urban areas.

Physicians recommended carrying posies of sweet-smelling flowers for protection. The plague doctor’s iconic bird-like mask wasn’t just creepy – its long beak held aromatic herbs to purify the air they breathed! Cities tried combating disease by burning massive bonfires to cleanse the atmosphere.

While completely wrong about the mechanism, miasma theory accidentally led to some positive public health measures like improved sewage systems and ventilation. Germ theory wouldn’t replace these ideas until the late 19th century.

8. The Moon’s Control Over Madness

Full moon tonight? Better watch out for unusual behavior! Enlightenment physicians firmly believed lunar phases directly affected human minds, especially triggering madness during full moons.

This widespread belief gave us the term “lunatic” – from “luna,” the Latin word for moon. Asylum records often noted moon phases alongside patient symptoms, and some doctors even scheduled treatments according to lunar calendars. The moon’s gravitational pull on Earth’s water led people to reason it must similarly affect the brain, which they thought contained significant fluid.

Interestingly, some mental hospitals reported increased patient agitation during full moons, though modern science attributes this to better visibility at night rather than lunar influence!

9. Witchcraft Amid Scientific Progress

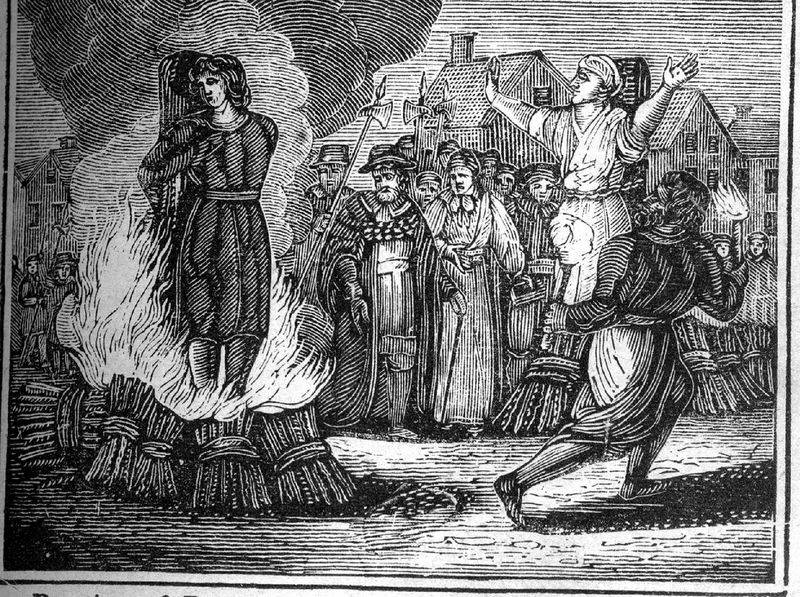

Surprisingly, witch-hunting continued well into the supposedly rational Enlightenment! While thinkers championed reason, ordinary people and even some intellectuals still firmly believed witches caused illness, crop failures, and other misfortunes.

The infamous Salem witch trials occurred in 1692-93, right as Enlightenment ideas were spreading. Even in 1775, Germany executed Anna Maria Schwägelin as a witch. Accusers often targeted elderly women, especially widows or those with knowledge of herbal medicine.

Enlightenment philosophers gradually challenged these superstitions. Christian Thomasius’s influential 1701 book argued against legal persecution of witches, helping end witch trials in Prussia. Still, folk beliefs about witchcraft persisted long after official trials ended.

10. Vital Force Animating Life

What makes living things different from non-living matter? Many Enlightenment scientists insisted it was an invisible “vital force” that couldn’t be explained by mere chemistry or physics!

This concept, called vitalism, proposed that living organisms possessed a non-physical essence that gave them life. Vitalists believed this mysterious force explained why scientists couldn’t create life in laboratories. Medical schools taught that diseases resulted from disruptions to this life force, requiring special treatments to restore its flow.

Even after Friedrich Wöhler accidentally synthesized urea (a biological compound) from inorganic materials in 1828, vitalism persisted for decades. The theory finally faded as biochemistry advanced, showing life processes followed the same chemical rules as non-living systems.