Shinto, Japan’s oldest religion, continues to shape the country’s cultural identity even today.

At its heart, Shinto offers a unique way of seeing the world where nature, community, and spirituality blend together seamlessly.

The following principles form the foundation of this ancient belief system that has guided Japanese life for centuries, connecting people to both their natural surroundings and their ancestors.

1. Reverence for Kami: The Sacred Spirits of Everything

The natural world pulses with divine energy in Shinto belief. Mountains, trees, rivers, and even everyday objects harbor kami—sacred spirits deserving respect and honor. Unlike gods in other religions, kami aren’t perfect beings but rather forces with both positive and negative qualities.

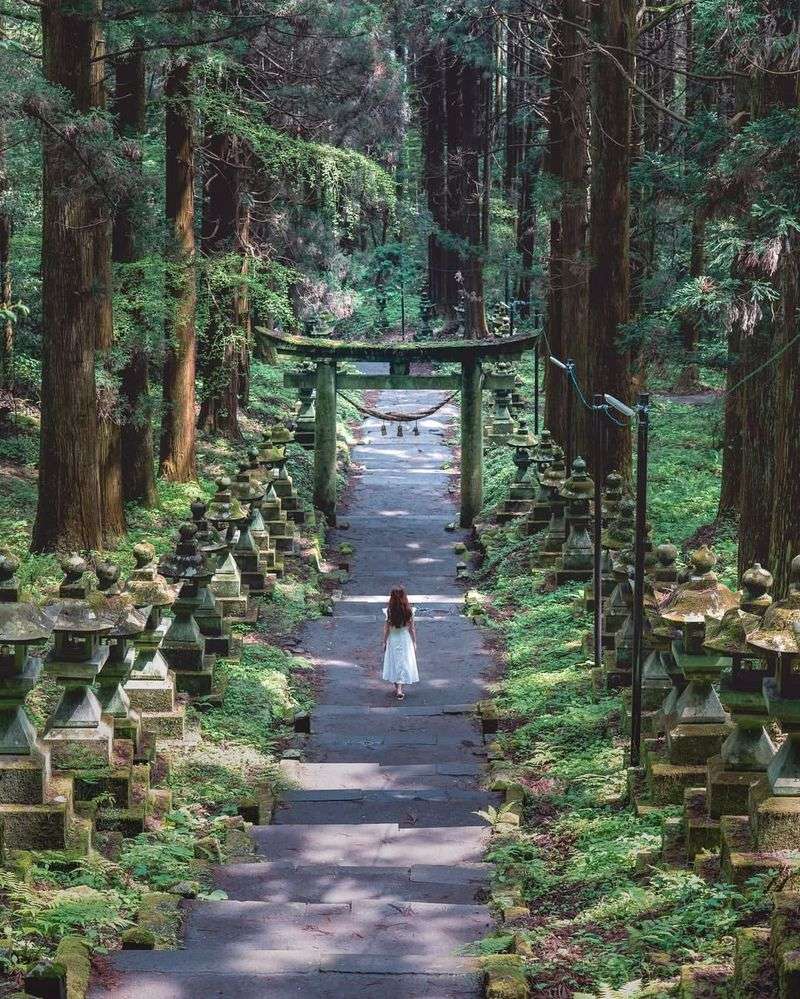

When walking through a forest or passing a remarkable stone, Shinto followers might bow slightly, acknowledging the presence of something greater than themselves. This perspective transforms ordinary landscapes into sacred spaces filled with wonder.

Ancient stories tell of powerful kami like Amaterasu, the sun goddess, whose mythology remains central to Shinto practice and Japanese cultural identity.

2. Purity and Purification: Cleansing Body and Spirit

Water flows at the entrance of every Shinto shrine, inviting visitors to wash their hands and rinse their mouths before approaching sacred spaces. This ritual, called temizu, represents the washing away of impurities that accumulate through daily life.

Salt serves as another powerful purification element in Shinto. Sumo wrestlers throw salt before matches, and small piles appear at doorways during times of transition or after unfortunate events.

The concept of kegare (impurity) contrasts with the ideal state of purity. Physical dirt, illness, death, and negative emotions all create spiritual pollution that regular purification rituals help remove, restoring harmony between people and the spiritual world.

3. Living in Harmony with Nature’s Rhythms

Cherry blossoms bursting into bloom signal more than just spring’s arrival—they embody the Shinto principle of living in harmony with nature’s cycles. Seasonal festivals called matsuri mark these important natural transitions, inviting communities to celebrate together.

Many Shinto shrines nestle against mountainsides or stand beside ancient trees, physically demonstrating the religion’s deep connection to the natural world. The most sacred natural features often receive special recognition with shimenawa—twisted straw ropes that mark boundaries between ordinary and sacred spaces.

Rather than trying to conquer nature, Shinto teaches gratitude for its gifts and respect for its power, encouraging followers to find their place within the greater natural order.

4. Makoto: The Power of True-Hearted Sincerity

“The kami value a sincere heart above elaborate offerings.” This saying captures makoto—the principle of absolute sincerity that forms the spiritual backbone of Shinto practice. A simple prayer offered with complete honesty outweighs the grandest ceremony performed without true feeling.

When visiting shrines, worshippers clap twice before praying, symbolically awakening both their own hearts and alerting the kami to their sincere presence. This straightforward approach reflects Shinto’s emphasis on authenticity over complexity.

Makoto extends beyond religious contexts into everyday Japanese life, where genuine intention matters more than perfect execution—a refreshing perspective in our often performance-focused world.

5. Honoring Ancestors as Living Presences

Family altars glow with tiny flames in many Japanese homes, marking spaces where the boundary between living and deceased family members thins. Ancestors aren’t considered gone but rather transformed into protective spirits who continue participating in family life.

During Obon festival, families welcome ancestral spirits home with lanterns and special foods, maintaining connections across generations. Small offerings of rice, sake, or favorite treats regularly appear on household altars, nourishing these important relationships.

This ancestral reverence creates a sense of continuity and belonging. Children grow up understanding they’re part of something larger than themselves—a human chain extending backward through time and forward into the future.

6. Sacred Rituals: Connecting Worlds Through Ceremony

Hands wave gracefully through the air holding a gohei—a sacred wand with paper streamers—as a Shinto priest performs harae, a ritual cleansing ceremony. Such precise movements have remained largely unchanged for centuries, creating bridges between everyday reality and the realm of kami.

The sound of a priest striking a large drum reverberates through shrine grounds during important ceremonies, helping participants shift their awareness from ordinary concerns to sacred time. Offerings of rice, sake, and salt accompany most rituals, symbolizing the sharing of life’s essentials with spiritual forces.

Even everyday actions can become ritualized in Shinto practice—the careful folding of clothing or mindful preparation of food transforms mundane tasks into opportunities for spiritual connection.

7. Beauty in Simplicity: The Aesthetic of Sacred Spaces

Unpainted cypress wood weathers to silver-gray at Ise Jingu, Shinto’s most sacred shrine, rebuilt every twenty years using ancient techniques. This deliberate simplicity reflects the Shinto aesthetic where unadorned natural materials speak more profoundly than elaborate decorations.

Empty space holds as much importance as physical elements in shrine design. These intentional voids create room for spiritual presence and human contemplation—a physical manifestation of the Shinto worldview where the seen and unseen coexist.

The distinctive torii gates marking shrine entrances embody this elegant minimalism with their basic post-and-lintel design, instantly recognizable yet profoundly simple. Through this aesthetic restraint, Shinto spaces invite visitors to look beyond surface appearances to deeper spiritual realities.