Across the world, countless traditions once formed the backbone of cultural and spiritual life.

These sacred practices connected people to their ancestors, to nature, and to deeper meanings beyond everyday existence.

Yet as time marched forward, many of these rituals faded into the background, pushed aside by modern conveniences, technological advances, and changing values.

Let’s rediscover these forgotten traditions that once held tremendous significance for communities around the globe.

1. Dream Weaving by the Ojibwe

Before dreamcatchers became trendy decorations, they served as powerful spiritual tools for the Ojibwe people of North America. Parents would craft these intricate web-like objects from willow hoops and sinew, hanging them above children’s beds to filter nightmares.

The good dreams would pass through the center hole to reach the sleeping child, while bad dreams would get caught in the web until morning sunlight dissolved them. Each dreamcatcher represented a family’s unique protection symbols and prayers.

As tribal communities faced displacement and cultural assimilation, the profound spiritual significance of authentic dreamcatchers diminished, though their physical form lives on as decorative souvenirs.

2. Māori Fire Walking Ceremonies

Walking barefoot across scorching hot coals wasn’t just a feat of endurance for Māori warriors—it was a sacred ritual demonstrating spiritual power and connection to ancestors. Young men prepared for weeks through fasting, meditation, and special prayers that would protect them during this extraordinary rite of passage.

Elders guided initiates through precise movements and breathing techniques believed to harness protective energies. The entire community would gather to witness these ceremonies, which reinforced tribal bonds and spiritual hierarchies.

Colonial powers actively suppressed such practices, viewing them as “primitive” or dangerous, despite the profound spiritual meaning they held for generations of Māori people.

3. The Banned Potlatch Celebrations

Among Pacific Northwest tribes like the Tlingit, the Potlatch wasn’t just a party—it was the cornerstone of their economic and social structure. Chiefs would host elaborate feasts where they gave away or even destroyed valuable possessions, demonstrating their wealth and generosity while redistributing resources throughout the community.

These multi-day gatherings featured ceremonial dances, oral history recitations, and the passing down of hereditary names and privileges. Songs, stories, and clan histories were preserved through these events, serving as living archives of cultural knowledge.

Canadian and American governments banned Potlatches from 1884 to 1951, seeing them as obstacles to assimilation and threatening to capitalist values of accumulation.

4. Himba Women’s Initiation Dance

In the arid landscapes of Namibia, young Himba women once participated in the Ohango dance—a coming-of-age celebration marking their transition to womanhood. Girls spent months preparing their appearance, coating their skin with a mixture of ochre, butter, and aromatic herbs that gave them a distinctive reddish glow considered the height of beauty.

The dance itself was a display of grace and endurance, sometimes lasting from sunset to sunrise. Mothers and grandmothers would sing ancient songs while teaching precise movements that had been passed down for countless generations.

Tourism has transformed many Himba practices into performances, with the deeper spiritual meanings and community significance gradually eroding.

5. Sacred Body Scarification of the Dinka

For centuries, Dinka youth in South Sudan underwent elaborate facial scarification as a transformative rite marking their entry into adulthood. Far from being merely decorative, these permanent markings—called gaar—identified one’s lineage, family history, and social standing within the tribe.

The ceremony itself was intensely spiritual, with tribal elders performing the cuts using specialized tools while invoking ancestral protection. Young men were expected to endure the painful process without showing discomfort, demonstrating the courage and resilience needed for adult responsibilities.

Modern medicine, changing beauty standards, and migration to urban areas have led many young Dinka to reject this ancient practice, though elders lament the loss of this identity marker.

6. Hopi Rain Summoning Dances

When drought threatened their crops in the parched Southwest, Hopi dancers transformed into kachinas—spiritual messengers between humans and the divine. Wearing elaborate masks and body paint, they performed precise, rhythmic movements that had remained unchanged for centuries, each step believed to call the life-giving rains.

Children learned these sacred dances from early childhood, understanding that their community’s survival depended on maintaining harmony with natural forces. Every detail mattered—from the eagle feathers representing wind to the turquoise symbolizing water.

Modern irrigation systems and climate change have altered the Hopi relationship with rain, though some communities still perform modified versions of these dances to maintain cultural continuity rather than as literal rain-making rituals.

7. Kazakh Eagle Hunting Partnerships

High in the Altai Mountains, Kazakh nomads once practiced berkutchi—the ancient art of hunting with golden eagles. More than mere hunting companions, these magnificent birds were considered family members, living inside the family’s ger (yurt) and developing deep bonds with their human partners over years of training.

A berkutchi would capture a young female eagle and spend years teaching her to hunt fox and wolf across the harsh Mongolian steppes. The relationship required extraordinary patience, with hunters developing unique calls and signals understood only by their bird.

After seven years, tradition dictated releasing the eagle back to the wild to breed, ensuring the continuation of both eagle populations and the hunting tradition itself—a cycle now broken as fewer than 100 eagle hunters remain.

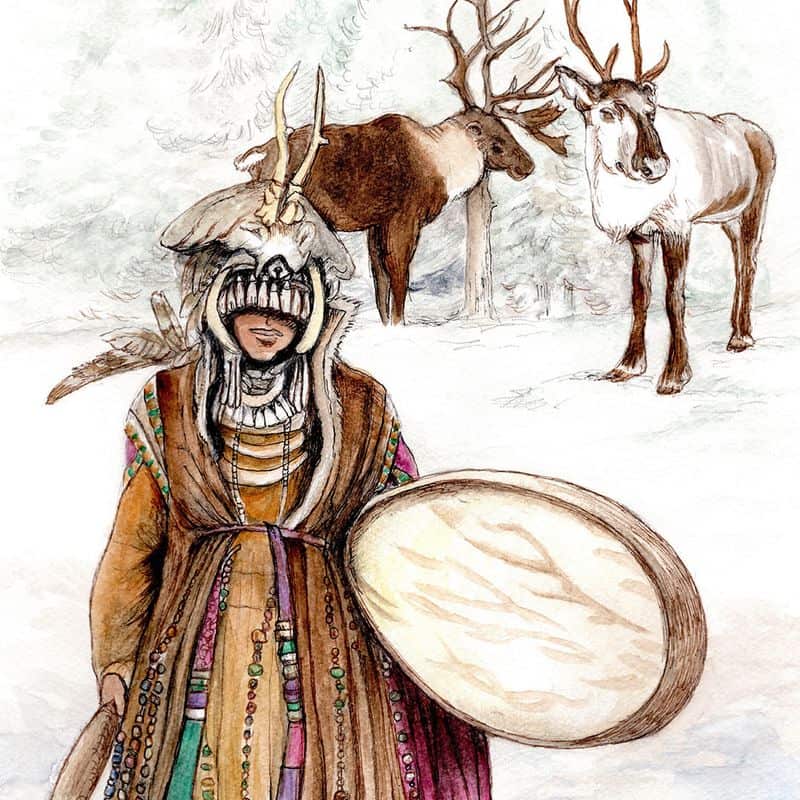

8. Forbidden Sámi Shamanic Drumming

The rhythmic beat of the goavddis (shamanic drum) once guided Sámi spiritual leaders through the invisible realms of their Arctic homeland. Crafted from pine wood and reindeer hide, each drum featured intricate symbols representing the cosmos, with the noaidi (shaman) using a T-shaped antler hammer to produce trance-inducing beats.

During ceremonies, community members gathered in sacred circles while the noaidi journeyed to other worlds, communicating with nature spirits and ancestors. These drums served as maps of the spiritual landscape, with painted symbols representing different realms and beings.

Christian missionaries systematically destroyed these drums during forced conversions, considering them tools of the devil—a devastating blow that severed the Sámi’s connection to their spiritual heritage.

9. Inuit Women’s Facial Tattoos

The delicate blue lines adorning Inuit women’s faces weren’t simply decorative—they were living maps of personal and cultural identity. Using a bone needle and thread coated in soot or seal oil, elder women would stitch intricate patterns into a young woman’s skin during her first menstruation, marking her readiness for marriage and adult responsibilities.

Different regions had distinct patterns, with chin stripes, cheek circles, or forehead lines indicating specific tribal affiliations and family lineages. The process itself was a profound test of character, as the recipient was expected to remain stoic throughout the painful procedure.

Christian missionaries banned these tattoos as “pagan markings,” nearly erasing this embodied cultural archive until recent revitalization efforts by younger generations.

10. Polynesian Earth Oven Gatherings

Long before modern cooking methods, Pacific Islanders perfected the umu (earth oven)—a communal cooking technique that transformed meal preparation into a sacred social bond. Men would dig pits and heat volcanic stones until they glowed red-hot, while women prepared taro, breadfruit, and fish wrapped in banana leaves.

The entire village participated in this ritual, with elders teaching younger generations precise techniques while sharing oral histories and genealogies. Food cooked this way wasn’t just sustenance—it was believed to capture mana (spiritual power) from the earth itself.

Modern conveniences like gas stoves have largely replaced the time-intensive umu, though some communities still use them for special occasions rather than as the daily cooking method they once were.