Today, Christmas feels like it has always been the center of winter celebrations. Lights, trees, gifts, and familiar songs make it seem timeless and unchanging.

Yet history tells a very different story. For many centuries, Christmas was not the most important day of the year, and in some places it was barely celebrated at all.

Instead, other holy days and sacred festivals filled the winter calendar. Some were Christian, some were older traditions adapted into new beliefs, and some were meant to replace Christmas entirely.

These forgotten holy days shaped how people understood faith, time, and community during the darkest part of the year.

When we look back at these lost celebrations, we discover a world where winter held many meanings, and Christmas was only one option among many.

Midwinter Before Christmas Took Hold

Long before Christmas became widespread, midwinter was already sacred. Across Europe and beyond, people marked the shortest days of the year with festivals tied to survival and hope.

These celebrations focused on light returning, crops resting, and families gathering for warmth.

When Christianity began to spread, it entered a world that already had strong winter traditions.

Early church leaders did not immediately push Christmas as a major feast. In fact, for several centuries, the birth of Jesus was not widely celebrated at all.

Instead, Christians focused more on Easter and the resurrection. Birthdays were not seen as spiritually important.

Winter holy days that did exist were often tied to fasting, prayer, and preparation rather than joy or feasting.

In some regions, Christians continued observing older midwinter festivals, but gave them new meanings.

These days focused on reflection, repentance, and waiting rather than celebration.

Because of this, Christmas grew slowly. It competed with older sacred days that people were reluctant to abandon.

In some areas, church leaders tried to redirect attention away from popular winter customs they saw as pagan or distracting.

This led to the rise of alternative holy days that shaped the season in different ways, sometimes pushing Christmas into the background for generations.

Epiphany as the True Center of Winter Faith

One of the most important forgotten replacements for Christmas was Epiphany. In the early Christian world, Epiphany was often more important than December twenty-fifth.

Celebrated in early January, Epiphany marked the revelation of Jesus to the world.

It honored events such as the visit of the Magi, the baptism of Jesus, and his first miracle. In many Eastern Christian communities, Epiphany was the primary winter feast.

For these believers, Epiphany held deeper meaning than a birth story. It focused on identity and divine presence rather than infancy.

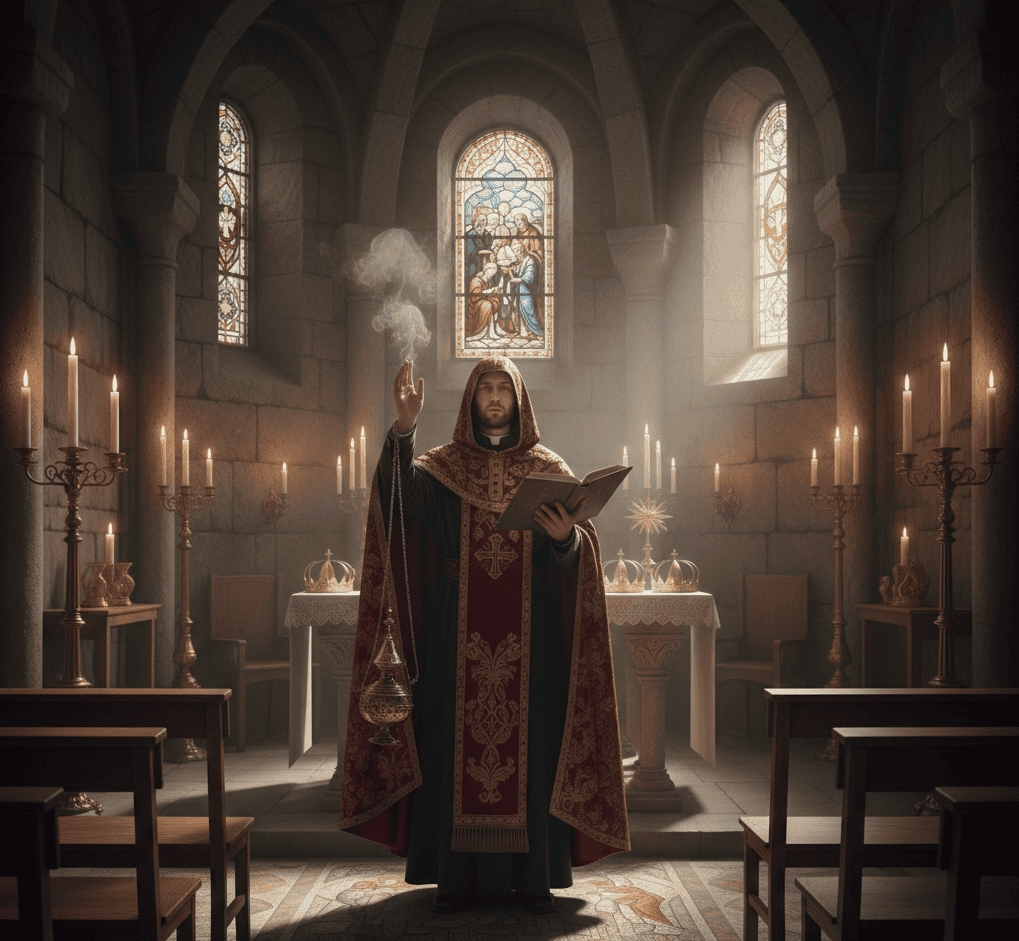

Churches were filled, rituals were elaborate, and entire communities gathered to mark the day.

In some places, Epiphany included public processions, blessings of water, and dramatic retellings of sacred stories.

Christmas, if celebrated at all, was often a smaller observance without much ceremony.

Even in Western Europe, Epiphany sometimes overshadowed Christmas. Gifts were exchanged on Epiphany rather than in December.

Children were taught that this was the true holy moment of winter. Over time, as Christmas gained popularity, Epiphany slowly lost its central role.

But traces remain in traditions like the twelve days of Christmas, which originally led toward Epiphany rather than away from it.

For centuries, Epiphany shaped how people understood winter faith. It reminded them that revelation mattered more than celebration, and meaning mattered more than comfort.

Only later did Christmas begin to replace it as the emotional heart of the season.

Fasting Seasons That Replaced Festivity

Another reason Christmas struggled to take hold was the presence of long fasting periods. In the early church, winter was often a time of restraint rather than joy.

One such period was Advent, which originally resembled Lent in its seriousness.

Advent could last weeks and involved fasting, prayer, and reflection. During this time, joyful celebrations were discouraged.

In some regions, Advent was so strict that celebrating Christmas itself felt out of place. The focus was on preparing the soul, not decorating homes or sharing feasts.

People attended church, gave alms, and avoided excess. Any celebration that felt too joyful was seen as distracting from spiritual discipline.

There were also local fast days and saints’ observances that took priority over Christmas. Communities might gather to honor a particular saint connected to protection, healing, or survival through winter.

These holy days met immediate needs. They felt practical and personal, while Christmas felt distant and symbolic.

In certain Protestant movements centuries later, Christmas was even rejected outright. Some reformers believed it had no biblical foundation and was too tied to old pagan customs.

In places like England and parts of early America, Christmas was banned or ignored for long periods.

Churches stayed open for regular worship, but there were no special celebrations. Other holy days focused on sermons, moral reflection, and obedience replaced the festive spirit entirely.

How Christmas Finally Took Over the Season

Despite resistance, Christmas slowly gained power. Church leaders began emphasizing the importance of the incarnation, the idea of God entering the human world.

Stories of the nativity became more detailed and emotional. Art, music, and drama helped make Christmas feel personal and warm.

Over time, these stories connected deeply with ordinary people. As societies changed, so did winter needs.

Feasting during winter made sense when food was scarce, and the cold was harsh. Celebrations offered comfort and hope.

Christmas began absorbing older traditions rather than competing with them. Elements of earlier midwinter festivals were woven into Christmas customs, making it familiar rather than foreign.

By the late medieval period, Christmas had become firmly established in much of Europe.

But even then, it shared space with Epiphany, saints’ days, and local holy observances. Only in the modern era did Christmas rise above all others.

Remembering the forgotten holy days that once replaced Christmas reminds us that traditions are not fixed. They grow, fade, and transform over time.

Winter was once filled with many sacred meanings, not just one. Christmas won its place, but it did so by standing on the quiet foundations of older beliefs.

These lost holy days still echo in our calendars, our rituals, and our sense that winter is a time for something deeper than ordinary life.

Ho sempre sentito una forte connessione con il Divino fin dalla mia nascita. Come autrice e mentore, la mia missione è aiutare gli altri a trovare l'amore, la felicità e la forza interiore nei momenti più bui.