The United States’ founding documents weren’t written as a sacred text, but they do carry spiritual language and symbolism that modern seekers can read with fresh eyes.

This isn’t about decoding secret societies or imposing a single religion.

It’s about noticing how the documents appeal to a moral order beyond government and how their symbols point to human dignity, unity, and ongoing growth – core ideas in contemporary spirituality.

1. Nature’s God

The Declaration opens by appealing to “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God,” then states that we are “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.”

Read plainly, it places natural rights prior to the state. Through a modern spiritual lens, this is a statement about intrinsic worth. Your value isn’t conferred by institutions; it precedes them.

That maps to present-day ideas of inherent dignity, consciousness, and the sovereignty of the person.

It’s a clean way to ground freedom without sectarian dogma: nature, a creator, and rights that exist whether or not a legislature approves.

2. Providence and Accountability Beyond Human Courts

The Declaration closes by appealing to the “Supreme Judge of the world” and relying “on the protection of divine Providence.”

Regardless of your metaphysics, the move is clear: the signers anchor their risk and responsibility in a larger moral frame.

Modern spirituality can translate this as alignment with a field of meaning or conscience bigger than ego or faction.

It’s a call to do hard things with trust, and to accept accountability that outlasts short-term wins – what many today would call living in integrity.

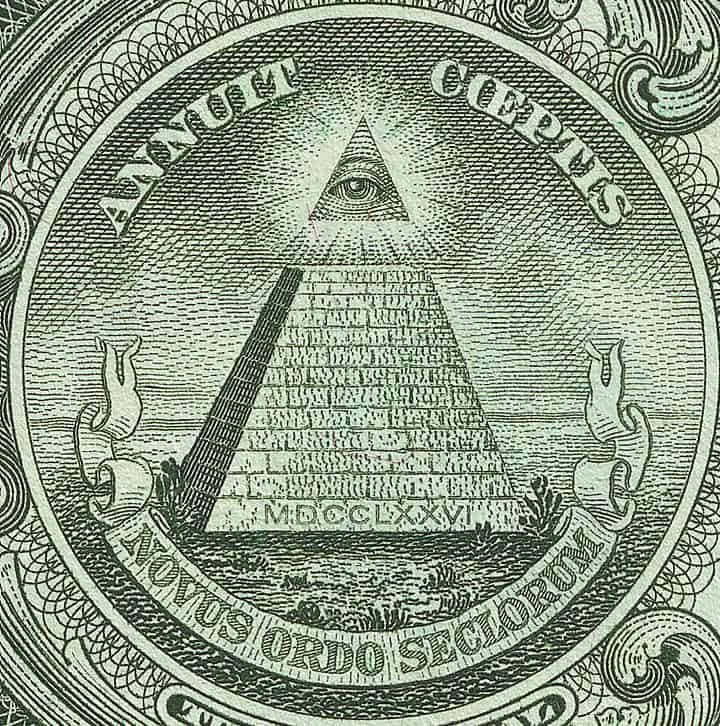

3. The Eye and the Unfinished Pyramid

On the reverse of the Great Seal, the Eye of Providence hovers above an unfinished pyramid.

The Latin mottos matter: Annuit Coeptis (“[Providence] has favored our undertakings”) and Novus Ordo Seclorum (“a new order of the ages”).

The government’s own description even notes the reverse is “sometimes referred to as the spiritual side of the seal.”

The pyramid has 13 steps – an intentional design choice – signaling work in progress, not completion.

For a modern reader, it’s a picture of collective awakening: build the base, leave room at the top for continued ascent, and invite guidance beyond narrow self-interest.

The same imagery appears on the $1 note, making this symbolism part of everyday life.

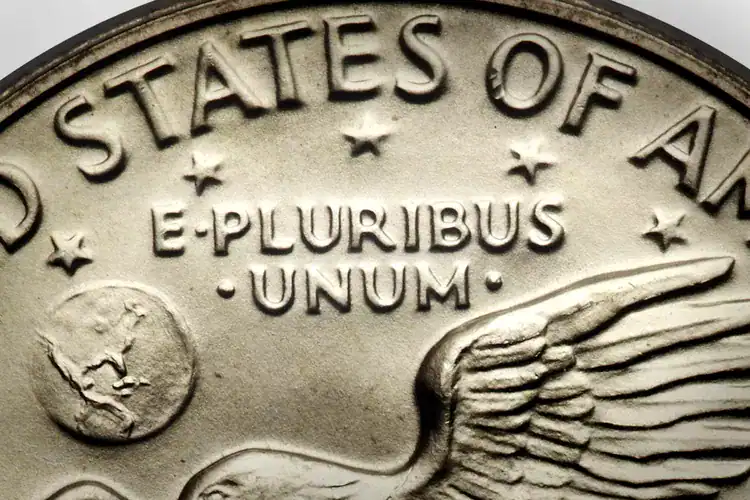

4. E Pluribus Unum: Unity Without Uniformity

The original national motto, adopted for the Great Seal in 1782, is E Pluribus Unum – “Out of many, one.”

It’s not a theological claim. It’s a social one with spiritual implications. Unity doesn’t erase difference. Instead, it integrates it.

In contemporary terms, this aligns with nondual thinking: the whole is real, and the parts matter.

For any modern spiritual practice that emphasizes interconnection – systems thinking, mindfulness of inter-being, compassion across lines – this motto is a succinct operating principle for a plural nation.

5. Thirteen Everywhere: A Ritual Count of Origins

The founders baked the number 13 into national symbolism.

13 stripes and stars; on the Seal’s obverse, the eagle holds 13 arrows and an olive branch with 13 leaves and 13 olives; the reverse pyramid has 13 steps.

Historically, it marks the original states. Spiritually, the repetition functions like a grounding mantra – remember your beginnings while you scale.

In modern practice, that’s a reminder to keep roots and purpose visible while institutions grow more complex.

It’s numerology only in a modest sense. The official sources list the count and its meaning plainly.

6. “We the People”: A Collective Intention Statement

The Constitution opens with “We the People,” not “We the States.”

That shift – credited by leading scholars to Gouverneur Morris in the Committee of Style – reframes sovereignty as emerging from persons together, not from governments above them.

As an intention statement, the Preamble names aims that read like values practice: justice, tranquility, the common defense, general welfare, and the blessings of liberty.

In modern spiritual language, it’s a group vow: we commit to these ends, and we’ll keep iterating structures to serve them.

The legal text is spare, but the ethical aspiration is not.

7. Radical Freedom of Conscience

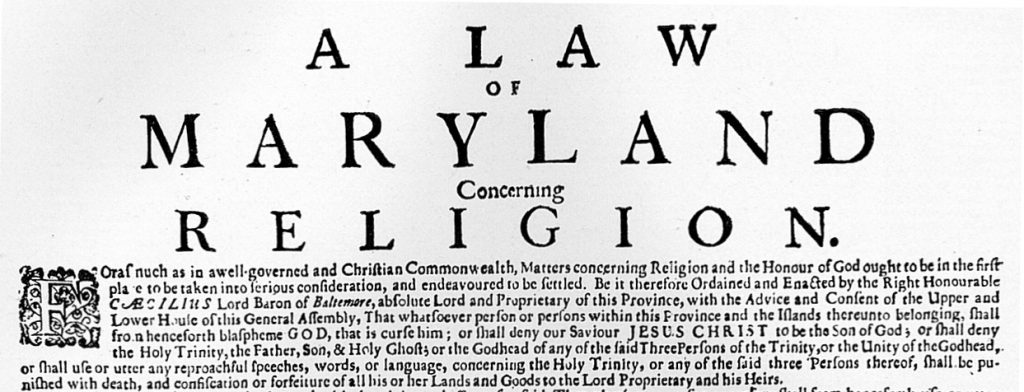

Article VI bans any “religious Test” for office.

The First Amendment bars an establishment of religion and protects its free exercise, alongside speech, assembly, and petition.

The state neither crowns a creed nor polices your interior life.

That separation is a precondition for modern spirituality to flourish – people are free to explore practice, meaning, and service without state interference.

At the same time, details in the Constitution reveal the framers working inside their culture’s calendar (“Sundays excepted” in the veto clause; the attestation dated “in the Year of our Lord”).

The point isn’t perfection. It’s direction. Rights of conscience are secured in law even as society evolves.

The Bill of Rights was proposed in 1789 and ratified in 1791, and its first words shield belief and non-belief alike.